Construction Operations

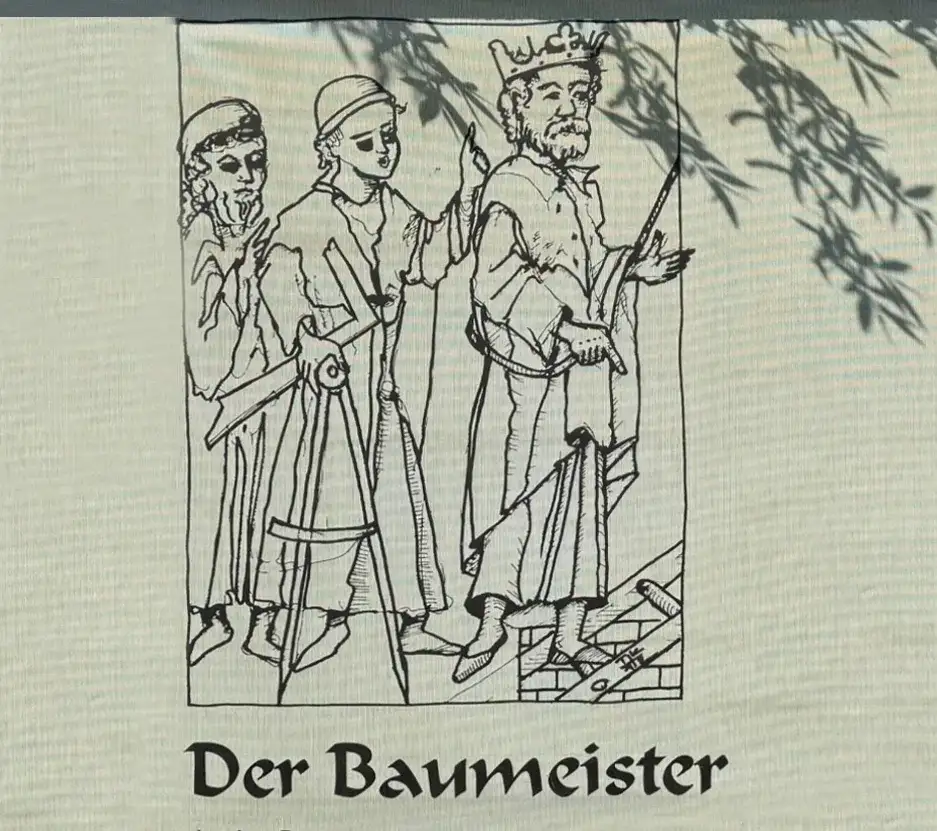

Master Builder

In the 11th century, he was responsible for construction techniques in castle building. A hundred years later, he had become a universally trained specialist, skilled in planning, designing, and building structures. He also assumed legal responsibilities.

Site Clerk

On major medieval construction sites, the site clerk supported the site manager and master builder, especially if the latter lacked proficiency in reading and arithmetic. He kept the books and produced cost estimates for piecework and material deliveries, working from the master builder’s plans and specifications.

Foreman

On any large site, the foreman was responsible for supervising the construction work. By the 14th century, he no longer worked manually but focused on planning, organising, and overseeing. For financial reasons, it became common for him to work on multiple sites at once.

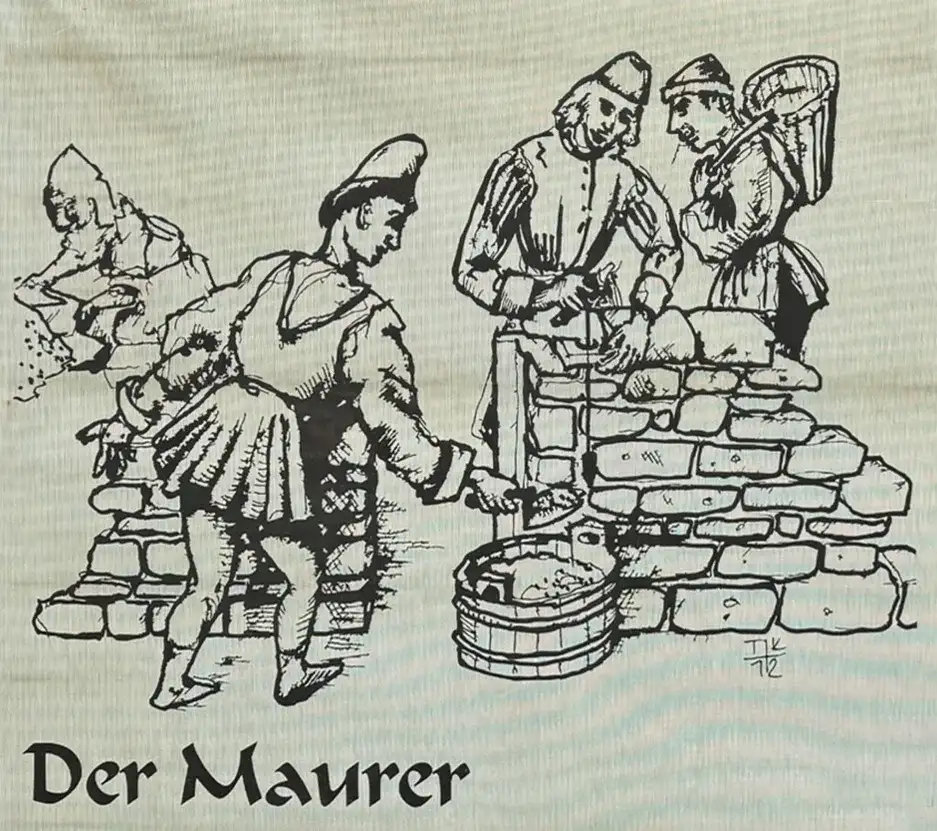

Mason

The roots of medieval craftsmanship lie in the monasteries. As stone construction became more widespread, monks and lay brothers passed their knowledge on to secular labourers. This gave rise to the trade of the muratores (masons). Together with the stonemasons, they laid building stones. Mortar was applied with a trowel, and the stones were aligned vertically or horizontally using a plumb line and mason’s cord.

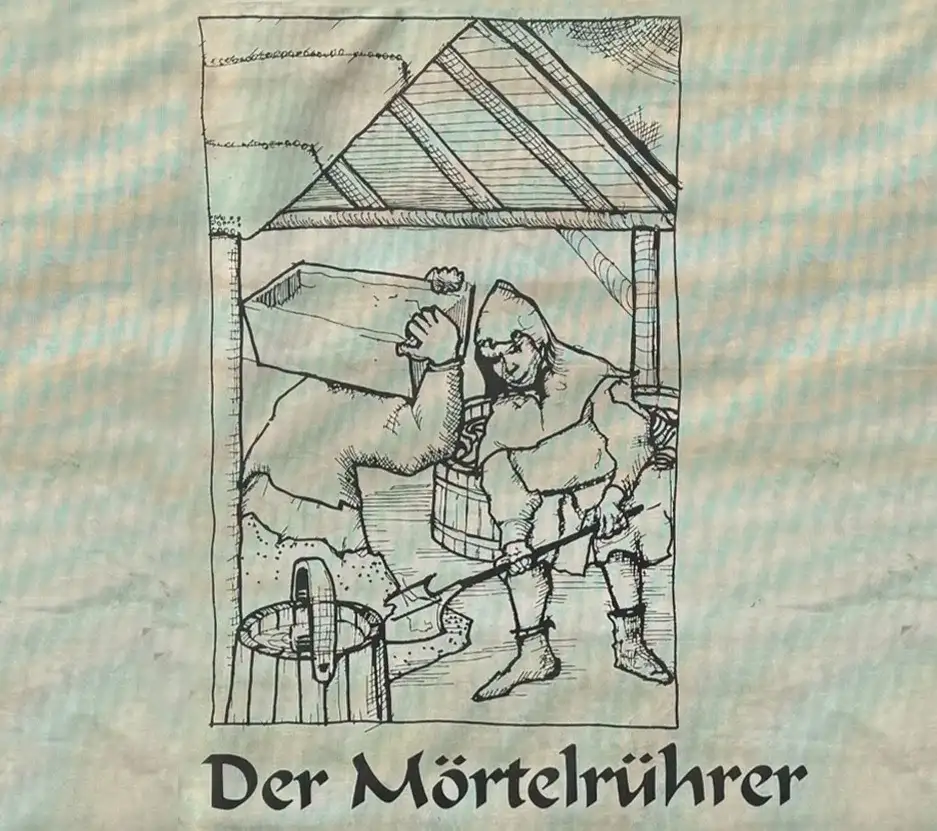

Mortarer

Although considered unskilled labour, mixing mortar was vital, as massive amounts of lime mortar were needed for building stone structures. On medieval sites, assistants sifted sand, slaked lime, mixed gypsum and mortar, and helped with brick and tile moulding.

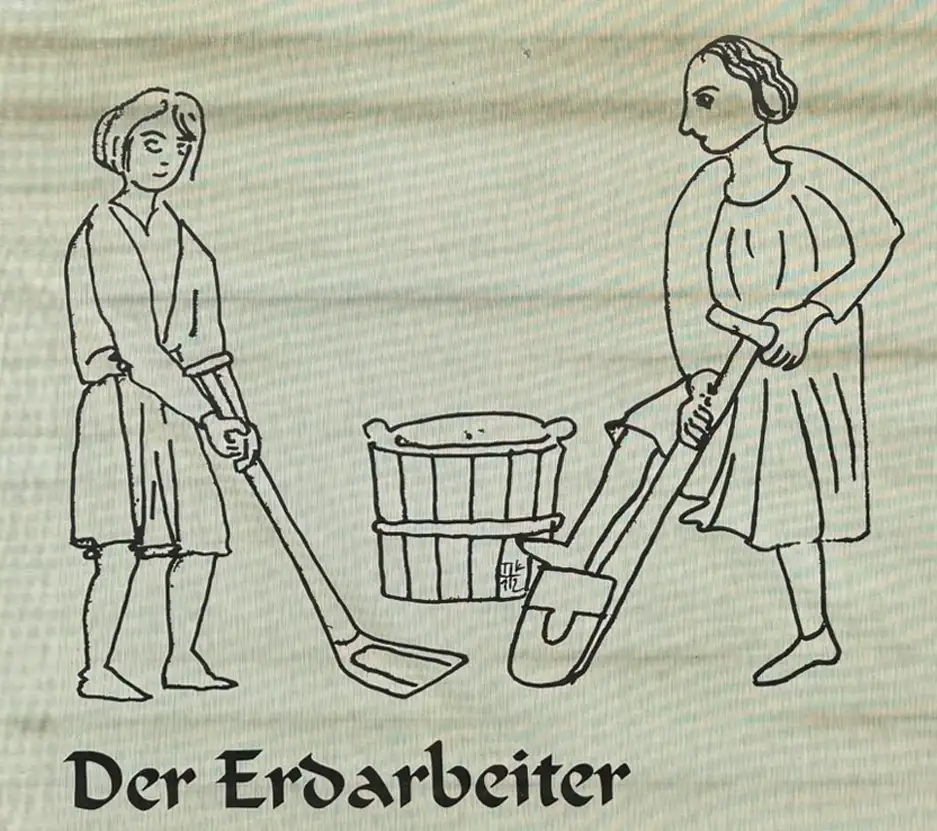

Digging Labourer (Earthworker)

He carried out all types of earthwork—digging foundation trenches, building embankments, and more. His was among the lowest-paid jobs on the site. Often a seasonal worker, he would also be employed in agriculture, so his availability depended on sowing and harvest times.

Blacksmith

His task was to make metal parts (e.g. fittings, hinges, locks, and keys). He was also responsible for maintaining all metal tools, including those for everyday use. Because of his work with fire and his ability to shape iron using hammer and anvil, he was sometimes feared and seen as a magician. For this reason, smiths were required to swear an oath upon completing their training not to engage in witchcraft.

Wainwright

In the Middle Ages, he produced wheel spokes, carts, wagons, sleds, and agricultural tools, and he was responsible for repairs. From the 14th century, wainwrights in larger towns organised themselves into their own guilds; elsewhere, they were incorporated into existing ones (e.g. carpenters or turners).